This is just one of several examples of lives interweaving and connecting throughout the book.

In researching his own family history, Philippe Sands discovers some surprising connections between his own family and that of Lauterpacht: Leon’s mother, Malke, who was to die at Treblinka, lived on the very same street in Zólkiew as the Lauterpachts, East West Street. Philippe Sands was aware growing up that his grandfather never wanted to talk about the past and even his mother seemed remarkably lacking in curiosity as to how she’d arrived in Paris as a baby unaccompanied by either parent. He’d arrived in Paris first, his baby daughter Ruth being brought later by an unknown person in July 1939 and his wife Rita not joining them until late 1941. When Philippe was a child, Leon was living in Paris, where he’d been since 1939 when he left Vienna. The book begins when Philippe Sands goes to Lviv to deliver a lecture and uses the opp0rtunity to visit the home of his Jewish maternal grandfather, Leon, who coincidentally had also grown up in Lviv and was born in the nearby town of Zólkiew.

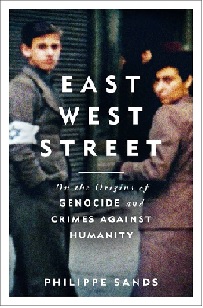

In this wide ranging and highly personal book, Philippe Sands, an international lawyer, shows us that it was at Nuremberg that the legal concepts ‘crimes against humanity’ and ‘genocide’ were first adopted and applied. In tracing the development of those legal ideas, he follows the life and career of the men who introduced them, Hersch Lauterbach and Rafael Lemkin respectively. Both of these men came from the area near the city of Lviv now in the Ukraine, formerly known as Lemberg and situated near the eastern border of the Austro- Hungarian Empire until its collapse during the First World War. What is probably less well known is what charges were actually on the indictment and what were the names of the crimes for which they were hanged. Many of us growing up in the 60s and 70s were aware that leading Nazi figures were prosecuted, found guilty and executed for their crimes at Nuremberg.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)